The macrocosmic portrait of redemption entails our Lord’s humiliation and exaltation. Touching His humiliation, He was conceived by the Holy Spirit in the womb of the Virgin, and so was endowed with every essential property of humanity, along with the common infirmities or frailties of our nature — excepting only sin. (see 2LCF 8) Concomitant with His humiliation is His exaltation, because even in His humiliation our Lord was reconciling the world to God and defeating the throws of sin, death, and the devil. (2 Cor. 5:19; Col. 2:15) Jesus did this, perhaps paradoxically, in His cruciform sacrifice, when He offered Himself up once for all. It was there when He declared, “It is finished.” (Jn. 19:30)

Following His death on the cross, our Lord’s body was buried and in His human soul, He went to the place of the dead. Quoting John Lightfoot, Dr. James Renihan writes, “The Soul of our Saviour therefore… descended into Hell, i.e. he passed into the state of the dead, viz. Into that place in Hades, where the souls of good Men went.”[1] Acts 2:27, a quotation from Psalm 16, reads, “For You will not leave my soul in Hades, Nor will you allow Your Holy One to see corruption.” Christ’s soul would not be left in Hades, or the place of the dead. Hence, between the day of our Lord’s death and His resurrection, His human body lay entombed and His human soul was in the place of the dead to proclaim the victory of the cross to all those “under the earth.” (Phil. 2:10; Rev. 5:13)

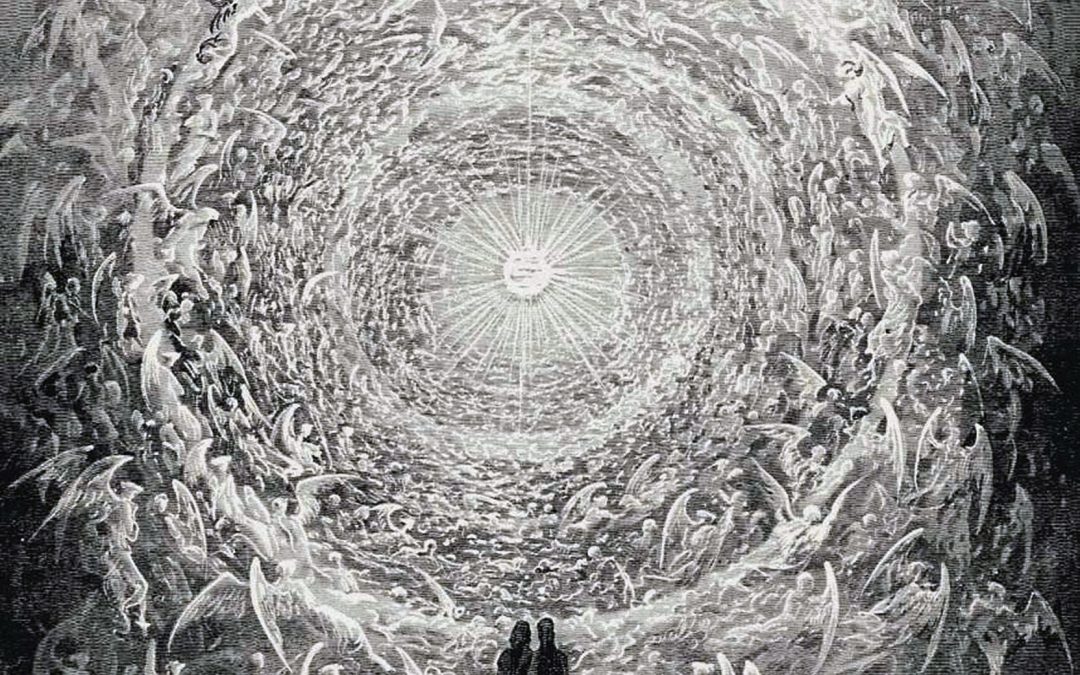

Not unironically, at the low point of the descent the ascent begins. Proclamation of victory under the earth, then proclamation of victory on the earth in the bodily resurrection. Finally, there is a proclamation of victory in glory as our Lord ascends and is seated at the right hand of power. This is the macrocosmic picture — the big narrative. The main event.

But I would like to submit to my readers that there are microcosmic pictures of redemption that occur throughout our Lord’s earthly ministry. It’s as if while He completes the big picture, He’s drawing the big picture on smaller canvases throughout His humble vocation. I’m almost certain that one of these smaller pictures occurs in Matthew 8. And it’s striking…

The Ordering of Details in Matthew 8

The ordering of details in Matthew 8 could not be more telling, but only if we view Matthew 8 as a literary-theological unit rather than a scattershot of disjointed stories. While there are changes in scenery and emphases in ch. 8, these changes occur in a logically progressive way. For example, Jesus descends the mountain in v. 1, in vv. 2-3 He begins healing people. This kingdom theme of healing those in need continues until v. 17. But from v. 17 to v. 18, there is no clear break. “And” is the transitional conjunction moving the reader straight into Jesus’ interaction with would-be disciples. In v. 23, Jesus and His true disciples board a boat, sail through a storm on the Sea of Galilee, and end up amid a bunch of tombs. Jesus scatters a horde of demons out of two possessed men into a multitude of swine only then to return to Capernaum.

The flow of events, therefore, seems to progress from somewhat normative circumstances in Judea, to a storm in the Sea of Galilee (which almost certainly typifies death), to the place of the dead, and then back to Judea.

At this juncture, I want to make a clarification. I am not claiming that the order of events as presented by Matthew is the same thing as the order of events as they historically played out. No doubt the authors of the gospels feel at liberty at times to rearrange the chronology of events for theological effect rather than chronological accounting. This is especially true of Matthew. (Cf. R. T. France, Commentary on the Gospel of Matthew) My point here is that the order of events as Matthew presents them under the inspiration of the Holy Spirit, whether they reflect the historical chronology or not, are significant and perhaps arranged to make a typological-theological point.

The Significance of Geography

The geography of Matthew 8 is just as important as the ordering of events. Not only do Jesus and His disciples travel from north to south, which may hint at a descent-like movement, but they also travel from the Promised Land into heathen territory — a place often thought to be inhabited by unclean spirits. And this particular location was no exception — the Gergesene tombs.

Keep in mind that the Jordan runs from Mt. Hermon in Lebanon through the Sea of Galilee and picks up on the southernmost side, running on to the Dead Sea further south. To cross Galilee — as Jesus and His disciples did — is to cross the Jordan. Commonly associated with death and life, crossing the Jordan into Gentile territory is a significant detail with a rich Old Testament background. For this reason, it serves a very important typological purpose throughout the Hebrew Bible right up to our Lord’s baptism in Matthew 3. Perhaps it also says something about our Lord’s intent to conquer the whole world, not just Canaan.

Further, one should not miss the watery environment. Water is typically associated with death (cf. Genesis 6-9; Jonah 2). A stormy deluge where the “boat was concealed by the waves” easily hearkens to a similar image. (Matt. 8:24) This is especially the case if we consider the Galilean excursion as a functional crossing of the Jordan into pagan territory.

While Jews may very well have inhabited what’s now the Kursi region, the presence of countless swine suggests a majority-Gentile population.

The most staggering geographical detail in Matthew 8 is the location to which Jesus very-intentionally brings His disciples — the Gergesene tombs. It’s quite literally a place of the dead. One can’t help but consider whether this dark scene anticipates the crucifixion of our Lord wherein He defeats death and the Satanic counsel at “the place of the skull,” or perhaps even His descent to Hades following His cruciform victory. I want to suggest the possibility of both.

These geographical details may seem interesting. But why should we think these specifics have any narratival significance at all? There are basically two reasons for why I think these details are meaningful. The text gives very specific geographical and circumstantial details, and this isn’t an accident. Matthew 8 begins by including Jesus’ descent from the mountain whereupon He preached the Sermon on the Mount. Not only is “the sea” mentioned, but specifics occur on the sea that shouldn’t be passed over. In v. 28, we are told that Jesus and His disciples arrived precisely at “the country of the Gergesenes.” We are told there were tombs there, a site that exists to this day. At the close of the narrative, we find Jesus returning to “His own city,” which was likely Capernaum proper up north. Matthew 8 is an event-filled, geographic-specific text.

Whereas our Lord’s mission was redemptive in nature, it is reasonable to suggest these people, places, and events in Matthew 8 serve a broader redemptive purpose rather than simply being happenstance resulting in interesting Bible stories. Matthew 8 is redemptively and theologically rich.

WHAT ABOUT HISTORICAL PRECEDENTS?

In Matthew Henry’s commentary on Matthew 8:23-27, speaking of the storm on Galilee, he says the following:

One would have expected, that having Christ with them, they should have had a very favourable gale, but it is quite otherwise; for Christ would show that they who are passing with him over the ocean of this world to the other side, must expect storms by the way. The church is tossed with tempests (Isa. 54:11); it is only the upper region that enjoys a perpetual calm, this lower one is ever and anon disturbed and disturbing.[2]

Henry clearly sees an allusion to “the upper region” and the “lower one.” Between the two, the upper region is altogether more desirable, being calm and peaceful in contrast to the place of the dead. Commenting on vv. 28-34, he writes:

The scope of this chapter is to show the divine power of Christ, by the instances of his dominion over bodily diseases, which to us are irresistible; over winds and waves, which to us are yet more uncontrollable; and lastly, over devils, which to us are most formidable of all. Christ has not only all power in heaven and earth and all deep places, but has the keys of hell too.[3]

Henry draws a straight line from the tombs to the “deep places” and “hell.” John Chrysostom seems to consider the scene at the Gergesenes as a foretaste of a more weighty teaching on hell in contrast to the kingdom of God:

Consider then all these things (for the words concerning hell and the kingdom ye are not yet able to hear), and bearing in mind the losses which ye have often undergone from your love of money, in loans, and in purchases, and in marriages, and in offices of power, and in all the rest; withdraw yourselves from doating on money. For so shall ye be able to live the present life in security, and after a little advance to hear also the words that treat on self-government, and see through and look upon the very Sun of Righteousness, and to attain unto the good things promised by Him; unto which God grant we may all attain, by the grace and love towards man of our Lord Jesus Christ, to whom be glory and might forever and ever. Amen. (Emphasis mine)[4]

Thomas Aquinas sees significance in the descent from the mountain at the outset of ch. 8. He writes:

It says then, and when he had come down from the mountain. That mountain is heaven; a mountain in which God is well pleased to dwell (Ps 67:17). Hence after he descended from heaven, great multitudes followed him; but emptied himself, taking the form of a servant, being made in the likeness of men, and in habit found as a man (Phil 2:7). Or, by the mountain is understood high teaching; your justice is as the mountains of God (Ps 35:7). Since he was on the mountain, i.e., since he led a high life, his disciples followed him. And when he had come down from the mountain, great multitudes followed him. And I, brethren, could not speak to you as unto spiritual (1 Cor 3:1).[5]

There is more work to be done in terms of retrieving the historical exegesis of Matthew 8 to see whether history bears witness to the same observations I’ve tried to make throughout this post. But I do think that there is enough historical precedent to responsibly chart a path forward in elaborating upon the imagery of Matthew 8.

CONCLUSION

To end, we saw the order of events in the text. I qualified that this order of events could either be chronological or theological (it’s probably theological more or less). Either way, the order is arranged — either by time or by Spirit-wrought theological inspiration — for a redemptive reason. Further, the geography and circumstances of Matthew 8 are enormously insightful in my opinion. Jesus goes from a mountaintop in Capernaum to a hellish landscape on the other side of Jordan, back to Capernaum. Lastly, there is at least some historical precedent for the direction I’m moving in my observations. I do think this is a text that could be further explored in both academic and churchly spheres, and I hope this brief post is but a finger pointing to the riches of this particular chapter.

RESOURCES

[1] James M. Renihan, Baptist Symbolics, vol. II, (Cape Coral, FL: Founders Press, 2022), 231.

[2] Matthew Henry, Matthew Henry’s Commentary on the Whole Bible: Complete and Unabridged in One Volume (Peabody: Hendrickson, 1994), 1651.

[3] Henry, Commentary on the Whole Bible, 1652.

[4] Chrysostom, St. John. The Homilies On The Gospel Of St. Matthew. Jazzybee Verlag. Kindle Edition. Loc. 7089.

[5] Thomas Aquinas, Commentary on Matthew. Aquinas.cc. C8.L1.n681.