Let me begin by saying: I am not using the term “gullibility” in a derogatory or intentionally offensive manner. Being gullible just means to be easily persuaded, which is not always a bad thing. Young children are often easily persuaded by their parents, and this is normal. A person may be easily persuaded by their most trusted friend. There is nothing wrong with this, per se. Gullibility occurs within the contextual framework of trust. If a group of people live closely with one another, spending their lives with one another, undergoing lifechanging experiences with one another, they are also likely to be gullible toward one another.

My Observation

Anecdotally, not statistically, I have gathered there to be two rather different responses to the current flow of information which comes by way of mainstream media. Before we begin, however, know that this opinionated observation transcends democrat or republican, blue or red, Biden or Trump. This is an observation of something seemingly occurring across both sides of the aisle, and it tends to do so along generational lines, although not perfectly.

For example, I have observed the silent generation, that generation following on the coattails of the greatest generation, seems to be either much less trusting of contemporary news media or at least less aware of what the news media currently reports on. The boomers, following the silent generation, tend to almost entirely embrace what the media reports and has an erudite ability to articulate social media and the interfaces required to use it. They are almost as in touch with the modern flow of information as are gen x and millennials. Of course, gen x’ers and millennials, not to mention their successors, i.e. gen z, are inundated not merely with a flow of information, but also various digital means of engaging that flow, all of which make Facebook look like the first wheel ever invented. But millennials and gen z seem to be much more reluctant to accept what the mainstream media says, writes, or shouts. They appear to be much less united on the issue of media credibility.

Assuming these observations are accurate to any extent, what would explain them? If these observations hold true for the general mean of even just one city or state, one should at least ask, Why? Since this is my experience, I have put some thought into answering that very question.

My Theory

Again, I should reiterate, lest I be misunderstood, that I am not claiming my observations to be universally applicable. Nor do I think that my theory will hold, or even be helpful, in every instance where these observations are made. I am a pontificating pastor forced to consider the causes of things for the good of my family and congregation. I am just a guy wrestling with the same issues we all face with the aim of glorifying God the Father and His Son Jesus Christ. Thus, I only ask that you at least consider what I have to say.

My theory revolves around generational, circumstantial, and psychological factors. That said, it is a lot more complex than this article makes it seem, and I could probably write an entire book on it. As I look at generations and their respective circumstances, so too will I mention the psychological effects from those circumstances. For example, the psychological effect of sparse access to mass media is probably less attentiveness to it. A mind with lousy media exposure is less conditioned to give attention to it.

The silent generation is either skeptical of contemporary news media, or aloof from it, because they hardly had access to such a thing, except perhaps by radio or print. They were not conditioned to “watch the news” and accept “journalistic reports” every week, let alone every day, hour, or minute. If they did receive the news, it was through newspaper once a month or so, or it was over the radio for 30 minutes in the evening. But even radio news wasn’t nearly as accessible as contemporary news. Radios were generally not portable, and if they were, they were on the back of a G. I. in Korea or Vietnam. The silent generation simply was not inundated with news, nor were they particularly conditioned to search it out throughout their day. Even if they wanted to, they probably wouldn’t succeed.

Their successor generation, on the other hand, the boomers, had much more access to the mainstream news. However, they were also the generation taking their first steps at the beginning of the space race while living under the threat of nuclear war… during the inception of the tech age. Tech dominated the boomer imagination in the 1970s with popular movies like Star Wars, and shows like the Jetsons and Lost in Space, beginning back in 1962 and 1965 respectively. For some reason, industry usually follows pop culture. And there was a looming excitement among boomers at the prospect of constantly developing technology. They went from CBs to bag phones, and from bag phones to cell phones; from records to 45s, from 45s to 8-tracks, from 8-tracks to cassettes, from cassettes to compact discs, and from compact discs to MP3s and cloud music like Pandora and Spotify. The boomer generation is a generation that has been subject to a level of never-before-seen Heraclitean change, almost for the entire duration of its existence. The psychological effect of this circumstance? A mental conditioning for technological advancement to be received as a desirable common good.

Perhaps the most important circumstantial change was the invention of the personal computer (PC) which arrived in the early 80s. The addiction to tech began with the PC and only progressed from there on out, reaching a climax in the “iPhone age,” which only emerged out of a tight tech race between the largest tech companies in the world in the early 2000s. The race between Jobs and Gates was only the first of many to come. And it was exciting! As tech developed, portable PCs in the form of tablets and phones were next on the horizon. Voice came first, then texting; and, just as lightning strikes, general internet access in the palm of the human hand became normal. Boomers were primed to accept this technology with glee because of the excitement produced by pop culture as early as the 60s, and the pattern of their own generational experience was nothing but technological development after development and a general adaptation to it. Their minds, at the level of imagination, were cultivated for the reception of this new technology, which explains their rapidly growing and continual dependence upon it, keeping pace with their children and their children’s children.

However, there is a two-pronged variable in the boomer generation. The media boomers found themselves exposed to in their earlier lives was both scarce and, in large part, real journalism. They received their news through mediums of either radio, television, or newspaper. And if they received it on television, it was only for an hour a day. Moreover, the news outlets were forced to report the main events affecting the country and the world because they didn’t have the luxury of 24/7 channeling, let alone constant accessibility through mobile devices and social media. The dynamics of how media was produced then versus how it is produced and disseminated now are almost entirely different. Yet, even so, boomers were generally primed for a seamless transition from the news of yesteryear to the “news” of today because of the factors mentioned above (among others).

Mix all the above in with the concept of the “cool parent” (also spurred on by pop culture, usually Disney), and eroding ethics put on steroids by the sexual revolution in the 50s and 60s, and we have the general mass of boomers making an effort not to coach their kids with regard to the new tech, but to embrace it for them, supply them with it, and follow them in eating the fruit from the technological tree. This tech is, after all, what we’ve all been hoping for! Moreover, media is, for the most part, reliable since it only ever reports national and world news. At least, it used to when it only had an hour’s worth of mass visibility per day! But because of the need for production to meet ever-increasing demand paired with the prospect of new technological ability, the current landscape boasts countless ways to receive media. This leaves conventional news outlets vying for dominance by using their now-24/7 channeling and web & app presence advantage as means to retain an audience through whatever catches the most attention. And little retains attention more than bad news, especially bad news that elicits the reactions of mass hysteria and fear.

All of this makes for an unassuming boomer generation caught off guard by the progress of the ensuing technological revolution, not to mention an ever developing slip in political and journalistic ethics motivated by all sorts of greed on the back end. Boomers do not usually question the news media, but this is because they weren’t accustomed to doing so since they grew up in an age of generally honest reporting. The most scandalous events were along the lines of JFK’s assassination or Watergate. Politicians and journalists were in a healthy competition with one another, and they rarely walked hand and hand down the same road. If they did, it was because there was a common enemy, like Lee Harvey Oswald, the Vietcong, or the Russians. This is why it should be no surprise that mainstream media appeals so often to Russian antagonism. They know their most faithful demographic has been conditioned in the 70s and 80s to loath the Russians and anyone in bed with them. Take an obscure political situation and oversimplify it with the terms Russia or Russian collusion, and you will control the narrative in the minds of those who grew up in constant fear of a Russian-caused hot war.

This is how the news mainly functions now, upon sentiment and emotion rather than upon the facts of the matter. The main hinge points, of course, are the unstoppable rise in media consumption, media competition to feed that rise in consumption, and at the political end, the Bush’s and the Clintons with the need for large-scale media coverups or distractions for shady drug deals in central America and endless wars in the Middle East. But I digress. This is not, after all, a history lesson, but a proposed explanation of what’s going on with COVID news and those who most dogmatically follow it. Long story short, the news has changed in both its form and matter, and the transitional generation spanning that change was the boomers, who had been conditioned to embrace it all.

The gen x’ers aren’t far behind the boomers in terms of their level of trust in the media. However, they, as well as many millennials, seem to be less dependent upon centralized media and more trusting and influenced by decentralized media coming through platforms like Facebook, Twitter, Instagram, Gab, and the latest TikTok. These platforms feature private citizens with first-hand video camera surveillance, personal experiences, etc. This has made it more difficult for centralized media to control a narrative, and it has also introduced a level of distrust, especially among millennials, because the two sources of information, centralized and decentralized, are often at variance with one another; hence the cross-platform mass censorship beginning late last year just after the election.

There has also been an emphasis placed upon the natural sciences and the scientific method in public schools, which I believe has had an affect on the millennial mind. The sentiment is often: If I can’t see it, I won’t believe it. This has led to an inevitable, and perhaps inadvertent, skepticism of information sources. Moreover, Christians, the largest religious demographic in our country, adhere to a competing source of authority often opposed to what modern media heads promote, the Bible. For these reasons and more, the country has been split down the middle by people who generally accept centralized media, and those who do not.

Conclusion

At this point, I am confident there is enough here to at least consider and think about. I will set down my pen and write another day, Lord willing. However, I humbly invite you to consider these things with me. Ask the simple question, Why do I believe what I believe? If you cannot answer that question, it may be time to either find out why, or find an alternate (defensible) belief. I find that personal experience is often the best crucible for testing the claims of any media outlet. If the news app on my phone reports a Godzilla attack on Kansas City while I all the while look at a Godzilla-free Kansas City skyline, I’m going to believe my experience of Kansas City over what my news app says about Kansas City.

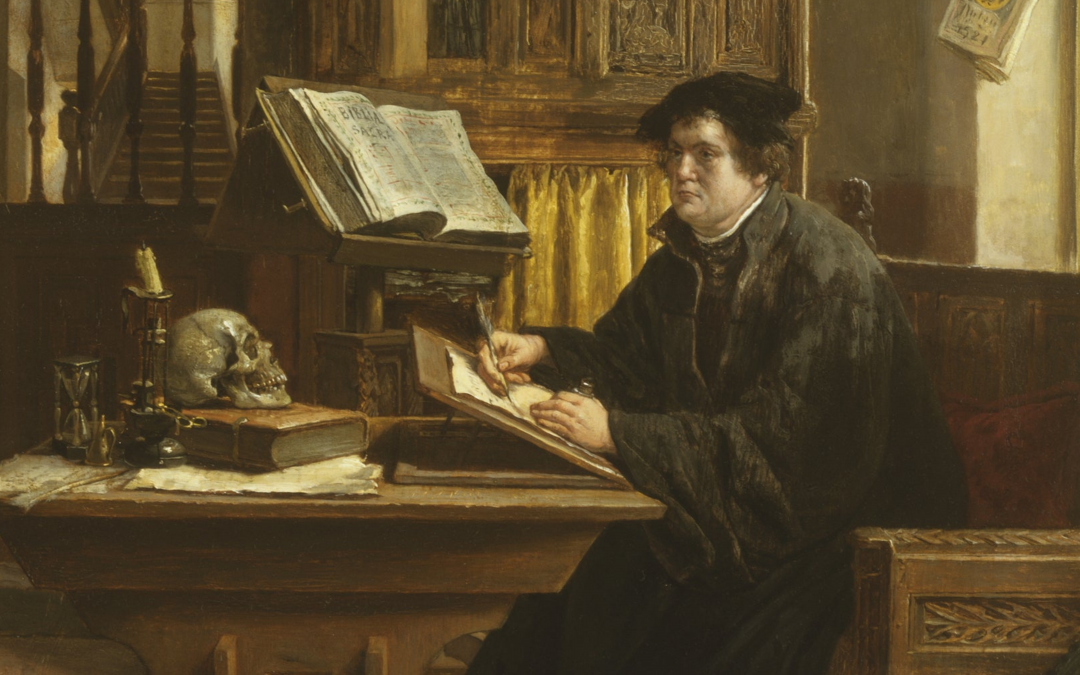

Ad fontes.